The events of this past week may one day be remembered not just as a military escalation, but as a coordinated collapse of restraint. Why is it so difficult for us to learn from the past, to retrieve lessons etched in history and implement them into our society?

The United States, for the first time, directly bombed Iran’s nuclear infrastructure. Fordow, Natanz, and Isfahan have been hit with GBU-57 bunker busters and submarine-launched cruise missiles. We cannot forget that whilst this occurs, Israel’s siege of Gaza continues, with reports that over 57,000 Palestinians are dead, aid convoys are deliberately and sadistically blocked, and civilian infrastructure is collapsing. In Ukraine, the war grinds on. 500,000+ casualties across both sides and the front line hasn’t meaningfully moved on in over a year.

We’ve seen moments like this before, when the world seemed poised on the precipice of self-destruction, teetering dangerously close to the edge of chaos. In 1914, alliances and nationalism overshadowed reason and plunged nations into the horrors of the First World War. In 2003, the invasion of Iraq showed us how pretext, veiled as a noble cause, could camouflage ambition and feed into cycles of conflict. And in countless other instances, history has shown us the same tragic rhythm: the blinding certainty of military confidence giving way, almost inevitably, to the haunting shadow of permanent regret.

Yet what sets this moment apart from those chapters of the past is not necessarily the scale of violence (although it is staggering) but the heavy, pervasive numbness that seems to blanket the global conscience. The silence speaks louder than words. The absence of a unified, worldwide outcry leaves an eerie void, as though humanity itself has grown too fatigued to respond. Condemnations, when they do emerge, come fragmented, ritualistic, and stripped of urgency and sincerity.

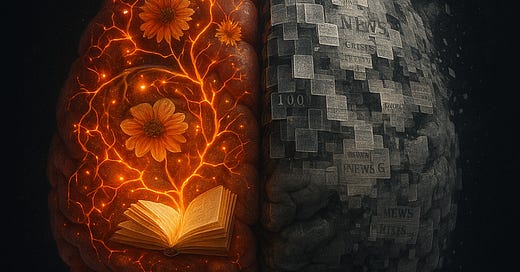

The media’s role in this numbness cannot be overlooked. Headlines flatten the complexity of events into bite-sized spectacles, erasing the rich contexts that might otherwise provoke outrage or action. Instead of fostering understanding, the relentless churn of the news cycle moves too quickly to grieve and too shallowly to warn. It leaves the public in a state of perpetual distraction. A fleeting engagement that dissipates as quickly as the next story appears. But we must ask: who decides what we see?

Increasingly, the answer is not journalists, but algorithms coded for attention. Designed to maximise engagement, they elevate spectacle over nuance, and outrage over empathy. Behind these platforms, still more power: billion-dollar newsrooms owned by corporate conglomerates, oligarchs, and dynasties whose interests rarely align with those they claim to inform.

There is something quietly sinister in this arrangement. Not conspiracy in the cartoonish sense, but something more effective. A system that ensures the loudest noise serves the least resistance. What does not trend does not exist, news which cannot be monetised is not mentioned. And so Gaza becomes a footnote, Ukraine fades into the ambient background and Iran registers as an alert, not a crisis. Meanwhile, celebrity scandal fills the silence, calibrated to make forgetting feel normal.

This is not just a failure of journalism. It is the commodification of attention, sold to the highest bidder, filtered through platforms whose only metric is velocity. And in that velocity, truth dissolves.

In this landscape of indifference, the bombs that fall in Iran, Gaza, or Ukraine echo not only through the rubble of their immediate destruction but in the hollow chambers of a world that refuses to listen. War itself risks becoming background noise in a society too numb to process its implications. This is the true tragedy of our time, not just the escalation of violence but the moral vacuum in which it unfolds, unchallenged and unremembered.

The Great Amnesia

What unsettles me most about this moment isn’t just the escalation, it’s how quickly it will be forgotten. Not by those under fire, but by us, the scrolling public, the distracted majority. The sleepwalkers of the so-called West. We don’t just fail to learn from history; we have designed a civilisation that no longer remembers it.

This is where my time-horizon theory begins. The idea that our collective attention span, our capacity to think across generations, to imagine a future beyond ourselves, has been systematically shortened. Not by some accident of technology, but by the architecture of modern life itself.

In our era of unprecedented acceleration, the very structures that once anchored our ability to think long-term have begun to disintegrate. Governments no longer legislate with a vision that spans decades; instead, their focus shrinks to the immediacy of quarterly results or fleeting election cycles.

For the average individual, overwhelmed by the sheer volume of daily responsibilities and a constant stream of notifications, the act of pausing to reflect has become a rare luxury. Most people encounter twenty sensational headlines before breakfast, only to forget them by lunchtime. Not because they are indifferent, but because genuine engagement requires something many can no longer afford: mental and emotional capacity.

One of the most overlooked consequences of wealth inequality lies in its impact on time and foresight. Wealth inequality does not simply create disparities in access to resources; it also creates a stark divide in access to mental and emotional bandwidth. For those struggling to make ends meet, living paycheck to paycheck, rising costs, crime, and structural unfairness dominate their daily existence. In such conditions, there is little room for long-term thinking, as individuals are trapped in survival mode. Survival demands urgency, and urgency has no tolerance for philosophical reflection or broader societal contemplation.

On the other hand, being truly rich extends beyond material possessions. It grants individuals the freedom to think ahead, to plan, to wonder, and to imagine the world not only as it is but also as it could be. This cognitive freedom, the ability to pause, reflect, and envision a better future, is a privilege that is increasingly monopolised by the few who hold the majority of wealth. Meanwhile, the masses are kept occupied with manufactured urgency, unable to break free from the cycle of immediate demands and engineered distractions.

As Yuval Noah Harari puts it:

“When a thousand people believe some made-up story for one month, that’s fake news. When a billion people believe it for a thousand years, that’s religion.”

The tragedy is that we no longer believe in anything long enough to make it meaningful.

This is the great amnesia. A civilisation disconnected from its past, incapable of stewarding its future, and drowning in a present that moves too fast to matter.

Memory

But memory can be reclaimed. Even amidst the persistent din of modern life, where attention is fractured into innumerable shards and meaning dissipates like mist in the rush of passing days, there remains hope. To reclaim memory is not merely to archive the past, but to create a conduit between what has been and what yet might be…a thread that ties the wisdom of experience to the promise of possibility.

In the writings to follow, I aim to explore this conduit. What would it mean, truly, to widen the aperture of our collective vision? To reconstruct systems that do not merely serve the fleeting demands of immediacy but reward the discipline of foresight? To imagine technologies not as instruments of distraction but as vessels of dignity facilitating deeper thought and richer engagement? And above all, to ask, without cynicism, what it would take for us as individuals, as communities, and as a civilisation to genuinely remember how to care.

Care, after all, is the foundation of meaning. It is the quiet heartbeat of actions that transcend mere survival and gesture towards preservation, creation, and connection. Somewhere beneath the cacophony of modern apathy and engineered urgency, I still believe that humanity retains this capacity for care - a deep, innate instinct not to destroy but to nurture, not to forget, but to remember.

The time-horizon, that fragile bridge between present and future, can be lengthened. This will not happen by accident or by inertia but through deliberate intervention, through the reimagining of systems that have come to prioritise forgetting over foresight. These systems have been designed, consciously or not, to favour the immediate over the enduring, the transactional over the transformative. To change them will require not just technical ingenuity, but moral courage and a willingness to challenge those who profit from entropy and who thrive on the commodification of distraction.

I do not believe this task can begin at the centre, within the entrenched systems of power that benefit from the status quo. Change is more likely to emerge from the margins, from those who dare to resist the apathy and who choose, against considerable odds, to remember. It begins with individuals who reclaim their ability to think expansively, who challenge the cultural inertia that equates convenience with progress, and who insist on imagining a future worth striving for.

I do not know if there is judgment after this life - but I hope, for all our sakes, there is memory in the next.

- AK x